Getting Your Bearings Part II: Beaches North of the Cape Fear River to Rich’s Inlet

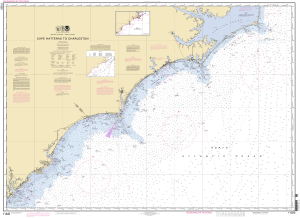

As we have seen, the mouth of the Cape Fear River is between Bald Head Island to the east and Oak Island to the west. Bald Head Island’s south beach runs east from the mouth of the Cape Fear River to the actual cape itself. This part of the shoreline runs more or less west to east, but at the cape the shoreline turns to the north and runs in a northerly or northeasterly direction for fifty or sixty miles. It looks like an almost 90-degree corner! Then it curves back around to the east again in a nice long arc until it reaches the next cape on the N.C. coast—Cape Lookout. Here’s a chart from Charleston, SC to Cape Hatteras. The pink arrow near the center is pointing at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, and the Cape is just to the east. Onslow Bay is to the northeast.

From Cape Fear to Cape Lookout is about 100 miles by the rhumbline or “as the crow flies”. A rhumbline is the navigational term for a constant heading between two points. IN this case, the heading is almost due northeast. If you were to sail the rhumbline from Cape to Cape, you would be out of sight of land for much of the time due to the curvature of the shoreline—the aforementioned arc. In fact, you’d be more than twenty miles offshore for much of the trip. From a normal boat, you can usually see the shore from inside ten miles, depending on the swell and the visibility.

If you were to depart from the rhumbline in a boat and follow the coastline instead, you would travel some 130 miles. If you were to drive from Cape Fear to Cape Lookout, you would drive about the same distance, but keep in mind that you can’t get to either cape by car. The closest you can get to Cape Fear by car is the Fort Fisher aquarium, and the closest you can get to Cape Lookout by car is Harker’s Island.

You can drive to N.C.’s third cape, Cape Hatteras, on the beach. Or at least close to it. At least you used to be able to. I’m not certain any more. They have restricted driving in Cape Hatteras National Seashore in order to protect nesting shorebirds, which has been very controversial. I’m not certain how much access is allowed at this point.

At any rate, you cannot drive to Cape Fear or Cape Lookout, but if you were to drive between the closest points it would take you about 3 hours. You would travel through three main cities: Wilmington on the south, Jacksonville in the middle, and Morehead City to the north. Another important town is Beaufort, but it’s much smaller. You used to be able to take a shortcut through Camp Lejeune Marine Base near Jacksonville, which saved a good twenty or thirty minutes, but they closed that road to the public after 9/11.

This entire stretch of coast between Cape Fear and Cape Lookout is called Onslow Bay, and when this blog focuses on the beach, it will usually focus on the beaches of Onslow Bay. Five counties abut Onslow Bay. From south to north, they are: Brunswick, New Hanover, Pender, Onslow, and Carteret. Brunswick’s coast on Onslow Bay is limited to eight or so miles of Bald Head Island’s East Beach. On the south side of Cape Fear is Long Bay, and on the north side of Cape Lookout is Raleigh Bay.

The barrier islands of Onslow Bay are listed in below in the lefthand column, and the inlets between them are listed in the righthand column. Again, they’re listed from south to north:

“Pleasure Island”

Masonboro Island

Wrightsville Beach

Figure Eight Island

Lea-Hutaff Island

Topsail Island

Onslow Beach

Hammocks Beach

Bear Island

Bogue Banks

Shackleford Banks

Lookout Bight

Corncake Inlet-New Inlet

Carolina Beach Inlet

Masonboro Inlet

Mason’s Inlet

Rich’s Inlet

Topsail Inlet

New River Inlet

Bear Inlet

Brown’s Inlet

Bogue Inlet

Beaufort Inlet

Barden’s Inlet

In this post, we’ll examine the first five islands and the inlets that divide them. That will bring us from Cape Fear up to the New Hanover-Pender County line. We’ll have to save the islands and inlets of Pender, Onlsow, and Carteret Counties for another day.

We’ve already mentioned Bald Head’s south beach, which lies to the west of the cape on Long Bay. Immediately north of the cape is East Beach, also a part of Bald Head Island. East beach runs north from the cape for about eight miles.

Pleasure Island

Then there is a little intermittent inlet that used to be called Corncake Inlet. To the north of that inlet is so-called “Pleasure Island”. Technically this land is an island, but it only became an island when the Army Corps of Engineers dug a canal between Masonboro Sound and the Cape Fear River in 1931. The name of the canal is Snow’s Cut. Immediately north of Corncake inlet is Fort Fisher. During the Civil War, Fort Fisher was the last major coastal fort to fall to the Union forces. It protected the port of Wilmington.

North of Fort Fisher are Kure Beach and Carolina Beach. Both of these beaches are on “Pleasure Island”, and there is no geographical feature separating the two. At the north end of Carolina Beach is Carolina Beach inlet. This inlet is still navigable for small vessels, but it is not maintained the way that it once was. In other words, the Corps doesn’t have enough money to dredge it anymore.

Masonboro Island

North of Carolina Beach Inlet is Masonboro Island. This island is one of the most important barrier islands in the Cape Fear Region because it is uninhabited and extremely beautiful. You can only visit Masonboro Island by boat. There are no houses or structures of any kind, and there aren’t any roads or cars either. It is a wonderful place for swimming, surfing, shelling, or camping out. Even in the middle of the summer, when it is most heavily visited, you can often walk along the beach for a mile or more without seeing another person. Masonboro Island is about eight miles from south to north. At the north end is Masonboro Inlet. Here is a picture taken on Masonboro Island during September and another picture on an unseasonably warm late-November day.

Masonboro Inlet is maintained as a navigable inlet by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This means that they keep it dredged to a certain depth. I believe it’s forty feet deep in some places. There are two enormous rock jetties protecting the inlet, and they stick out into the Atlantic about a quarter-mile or more.

The main reason that the Corps maintains Masonboro Inlet is that a U.S. Coast Guard Station is located just inside the inlet. However, the dredging also has other benefits. Larger commercial vessels, sportsfishing vessels, and pleasure craft can use the inlet. These demographics generate business for Wrightsville Beach and Wilmington. Also, every five or ten years when the Corps dredges, they pump the sand from the bottom of the inlet up onto Wrightsville Beach, which makes the beach a lot wider. That gives people space to sit and lie out during the spring, summer, and fall.

Finally, the inlet lets a lot more water flow in and out with the tides. This flushes the tidal estuaries and marshes behind Wrightsville Beach and Masonboro Islands, which is good because there is a tremendous amount of stormwater runoff that flows into these marshes from Wilmington and the surrounding developments. If it weren’t for the additional flow, these waters would be quite polluted, I’m afraid. Even as it is, they’re not as clean as we would like. As with most man-made changes to the environment, the jetties and dredging have less favorable consequences too—the increased salinity in the marshes renders them inhabitable for some species, and the jetties might increase erosion elsewhere. Of course, maintaining the inlet this way also costs a ton.

For long-distance cruising sailors, Masonboro Inlet is very useful. Many long-distance sailors like to sail from anchorage to anchorage in short hops rather than spending days at a time sailing offshore. At the same time, many such sailors prefer to avoid the treacherous shoals around Cape Fear. Masonboro Inlet offers a great access point for boats sailing up and down the coast. Coming up from the south, say Charleston, they can sail into the mouth of the Cape Fear River, and then motor up the river, through Snow’s Cut, and up the Intracoastal Waterway behind Masonboro. This “inside” route avoids Frying Pan Shoals and brings them to the mooring field in Bank’s Channel, just inside Masonboro Inlet.

Then, when they’re ready to weigh anchor and head for the next port, they can sail out of Masonboro Inlet into Onslow Bay and head for Beaufort Inlet to the northeast—the next good port of call. Sailing “outside” is preferable so long as the weather is nice, since you have a lot more room to maneuver, and the wind is usually better. The run to Beaufort takes 16 hours or so in a decent breeze in a good vessel.

Wrightsville Beach

To the north of Masonboro Inlet is Wrightsville Beach. Wrightsville Beach is about four-and-a-half miles from north to south. It’s oriented on a NNE by SSW basis. Wrightsville, like many of the barrier islands, is only a few hundred yards wide at its widest. Wrightsville is one of the most densely populated barrier islands, with thousands of structures and many year-round residents. Fortunately, they quashed the high-rise condo scheme before it really got going. There are basically four high-rises: two hotels and two condos, but they’re all ten stories or less, so they’re not too, too tacky. Nothing like Myrtle Beach or Gulf Shores. You learn to live with them.

Wrightsville Beach has a nice, laid-back surfer vibe for the most part, with an undercurrent of the well-off. There are a couple of surf stores, and a lot of the younger folks surf (as do plenty of older folks). There are two fishing piers and several marinas. Fishing is very popular, and there is a nice public boat ramp near the drawbridge. The old green Heidi Trask Drawbridge opens every hour on the hour if there are boats waiting, and it will open at other times if there are commercial or governmental vessels that need to come through. You don’t see as many of the latter category anymore since the ICW isn’t really maintained like it used to be, and containerized shipping and trucking has replaced a lot of the barge traffic.

The restaurant scene leaves a lot to be desired. This is primarily because the restaurants have to make all of their profit during the spring and summer, so they’re usually too busy and can’t afford to buy good ingredients. It’s a shame that we don’t have some really good restaurants on the water, but there are a few that are decent. For more of a fine-dining experience you have to go over the drawbridge to the mainland, or better yet to downtown Wilmington. Or, if you have access to a kitchen, just go to Mott’s Channel Seafood for delicious fish and shrimp, almost always caught the same day.

The third-oldest yacht club in the country is on Wrightsville Beach—the Carolina Yacht Club. There aren’t any yachts involved, but there are still close to a hundred little one-, two-, and three-main dingy sailboats. The main types are Sunfish, Lasers, 420s, Lightnings, and Optimists. The Carolina Yacht Club was founded in 1853, and back in the late 1880s and early 1900s, there were real yachts involved. The CYC has a number of very nice trophies won by its fleet from places like New York, Newport, and England. The only yacht clubs that are older are the New York Yacht Club and the New Orleans Yacht Club.

The northernmost mile of Wrightsville Beach used to be a separate island called Shell Island. It’s still referred to as Shell Island, kind of like a neighborhood of Wrightsville Beach. You can actually still tell where the inlet used to be because the island is narrower and low-lying.

At the north end of Wrightsville Beach is Mason’s Inlet. Mason’s Inlet is not maintained, and at low tide you can basically walk across it, although you might have to swim a little bit in the middle of the channel. About twenty years ago, Mason’s Inlet started creeping south the way that inlets naturally do. This went on for some years until it got quite close to one of those four high-rise resorts. This one is called Shell Island Resort, and it’s a hundred or so condos. Apparently when they first proposed to build it there, plenty of people pointed out that Mason’s inlet was moving south and would eventually wash it away. Somehow or another they got the permit and built it anyway.

By 1995 or so, the situation had become quite dire. At a full-moon high tide the water would come within a stone’s throw of the north side of the condo. Of course the property owners wanted the government to pay to solve the problem, but the government didn’t want to shell out the money. Some folks said to let the damn thing fall so as to teach everyone a lesson, but then cleaning it up would have been a huge mess too. The condo secured a permit for temporary sandbags, which held up all right but would have likely been washed away by a hurricane or a strong nor’easter.

Further complicating the issue, the island to the north of Mason’s Inlet—Figure Eight Island—is a private island. See below for more about Figure Eight. The property owners over there saw Mason’s Inlet more or less as their moat. Without it, ordinary general public types could just walk from Wrightsville Beach over to Figure Eight. Worse yet, once they made it over to the private island, they were technically allowed to walk up and down the littoral corrider below the high-tide line. This part of the beach is subject to the public trust doctrine.

Eventually everyone reached an agreement to share the costs, and the inlet was dredged. They dug a new channel a half-mile or so north, back where it had been decades earlier. They dug it out a humongous trench with bulldozers, leaving a little isthmus of sand holding back the ocean. Then, once it was all set, they waited until a full moon high tide and removed the sluice. It worked pretty well, and the water filled the new channel and started flowing through it.

Then they filled in the old channel down by the condo. I think they might have dredged and filled once or twice to make sure the new arrangement “took”, but to my knowledge it hasn’t required any significant maintenance since then. Wrightsville Beach gained a half-mile of sand on the north end, and Figure Eight lost a half-mile. The condo was saved, and the moat was restored. Most of Wrightsville’s new territory became a bird sanctuary, and small-craft boaters now have another nice inlet where they can go anchor on a pretty day and wade around.

Figure Eight Island

Figure Eight Island is to the north of Mason’s Inlet. As I mentioned, Figure Eight is a private island. That means that only homeowners and their guests can visit Figure Eight Island. They used to allow weekly rentals, but I’m not even sure that’s allowed anymore. Figure Eights was mostly developed in the seventies and eighties. Some of the houses are relatively modest; others are downright palatial. The homeowners are generally local or from upstate N.C.—especially Raleigh, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem. A few celebrities and titans of finance have houses there too. I’d estimate the island has 500 houses total, with maybe 50 full-time residents. It’s peaceful, no doubt. Very quiet. Very private.

There is only one way on and off the island, which is the drawbridge. One neat aspect of Figure Eight Island is that the drawbridge is a “pivot-style” bridge which rotates ninety degrees to open. You don’t see too many of those anymore. To the north of Figure Eight Island is Rich’s Inlet, which has itself been migrating south, undercutting few houses in the process. I’m afraid these folks won’t be able to build a coalition like Shell Island Resort did. I’ll try to get a picture up soon.

Get New Posts Via Email

Sign up to receive the latest posts via email.

Comments are closed.